Warwick's Citizens in the Great War: John Kakarago, Fireman 3rd Class, U.S. Navy

By Aaron Lefkowitz

When the United States had declared war on Germany in April 1917, there were many big questions that arose, such as how long will it take to raise an army, are there enough heavy weapons, are the American generals capable of this task, and above all else, how is America going to ship millions of troops across the Atlantic?

The answer to latter being by ship, countless gigantic troop transports making countless treks across the ocean, to bring the troops “Over There."

Men such as John Kakarago would take part in ensuring that these troops arrived as soon as possible.

Kakarago would be born in Russia on Christmas day 1895. At some point, he would immigrate to America, making his home in Orange County,New York.

Like many young men searching for adventure, he enlisted at the Navy Recruiting Station Brooklyn on June 6th, exactly two months after the U.S. declaration of war. Kakarago’s rank would be Fireman 3rd Class, which held a different definition in the Navy.

As most ships at the time were coal powered, Firemen were enlisted seaman responsible for the ship’s propulsion system.

He would serve first on the USS South Carolina, a dreadnought battleship, though this was only for three days, before being transferred to the USS Illinois, another battleship, where he would remain until August 31st.

His longest assignment would be on the SS President Grant, a German merchant ship, seized and renamed for President Ulysses S. Grant, and used as a troop transport, carrying exactly 40,104 servicemen to France, and 37,025 back, over 16 round-trips.

The next part of Kakarago’s service is great mystery, due to literally only one document existing on his service. On January 17th, 1918, he would be transferred from the Grant to USN Base Hospital 5 in Brest, France. He would spend three months and 10 days there, before dying on April 27th, more than a month before American troops saw their first battle.

No official cause for his death is listed, though reasonable theories exist.

Just is the case nowadays, if a virus comes onto a crowded ship, like the Grant, it will spread like wildfire.

That virus would be the Spanish Flu, which claimed more American troops than combat, many dying before they set foot on French soil.

The other main theory is that he was severely wounded in an accident as propulsion systems were very dangerous, while working on the Grant, which he succumbed to months later.

Either theory is plausible, but without any supporting details, they remain merely theories.

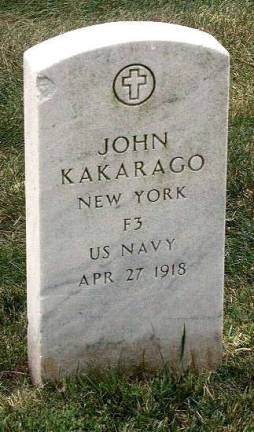

While most men, who died in service, where either buried in France or sent home to their loved ones, Kakarago’s final destination was a bit nicer. For reasons unknown, his remains would be transferred to Arlington National Cemetery in 1920.

Considering that only the most honorable and distinguished of soldiers are buried in Arlington, Kakarago’s service certainly had been well-merited.

Due to the scale of documentation of the Great War, it is not unheard of for official military documents to have inaccurate information, such as date of death or even hometown.

Such is the case of Kakarago, who is officially listed by the U.S. Government and Military as a resident of Chester, though Chester does not record him as such, nor have him on their memorial plaque.

This of course, posed the simple question: “If he isn’t Chester’s, then which town calls him it’s son?”

It's a question which perplexed me until the answer was sent to me by email. William Grohoski, a member of the American Legion Post 377 Goshen, had sent me a photo of Florida’s WW I service calendar, listing all of the names of its citizens in the service, and there was Kakarago.

Upon further research, he is listed on Warwick’s plaque as “Kakaryga, John,” ensuring that he, too, is remembered by the community, which claimed him, though under a different name, due to a spelling mistake.

While Kakarago, held the humble rank of Fireman 3rd Class, working well away from the combat or glory, his service was indeed absolutely vital. Only massive ships like the President Grant had the capability to move enough troops over to give the Allies, the numbers needed to beat the Germans.

While the Navy never saw combat during the Great War, they did allow the Allies to firmly grasp naval dominance, a major advantage for winning, by keeping troops and supply coming at a steady rate.

Kakarago's contributions are honored with his internment at Arlington, an honor, that many service members desire as an eternal monument for their service to the United States.