The 1918 – 1919 Influenza Epidemic impact on Warwick

Warwick. The current COVID-19 pandemic is dwarfed so far by the Spanish Flu Pandemic.

According to the National archives. World War I claimed an estimated 16 million lives.

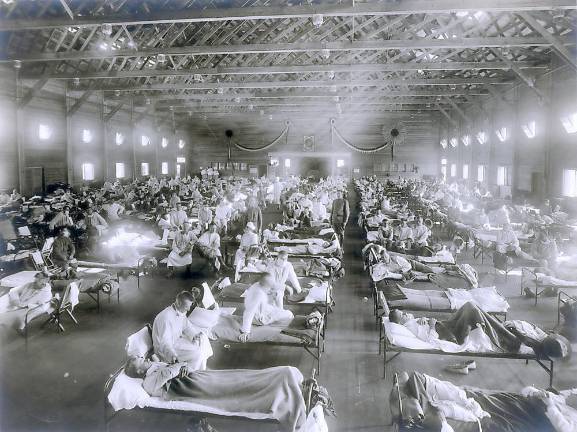

The influenza epidemic that swept the world in 1918 and which lasted 15 months, however, killed an estimated 50 million people, including about 675,000 people in the United States. The population of the country in 1919 was 104.5 million people.

Within months, it had killed more people than any other illness in recorded history.

And it was rampant in both urban and rural areas.

The plague emerged in two phases. In late spring of 1918, the first phase, known as the "three-day fever," appeared without warning.

Few deaths were reported and victims recovered after a few days.

But when the disease surfaced again that fall, it was far more severe. And at that time we did not have antibiotics, antivirals, ICU-level care, or even know that flu is caused by a virus.

An overlooked part of American history

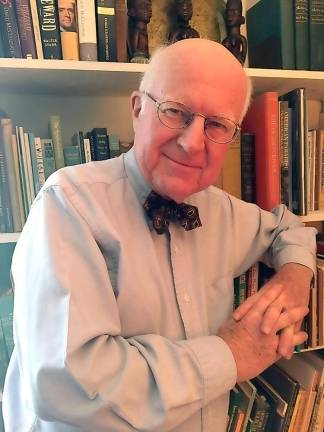

Town of Warwick Historian Dr. Richard Hull, who served as a Professor of History at New York University and taught courses in the history of pandemics, hosts a weekly radio program, “History Alive,” on WTBQ (AM 1110, FM 93.5).

Although many people couldn’t imagine how quickly the current COVID-19 pandemic would spread, Hull suspected early that it could and scheduled a program on the subject to air March 9 and again on March 23.

During the broadcast he explained that both national and local newspapers did not provide much information on the subject. To maintain morale, World War I censors minimized early reports of the impact of the illness. Public health officials, law enforcement officers and politicians also had reasons to underplay the severity of the pandemic for fear that full disclosure might embolden the enemy and also cause panic.

The influenza epidemic of 1918 has also been overlooked in the teaching of American history.

“In the beginning, it was not taken seriously here,” said Hull. “Most of the homes built in Warwick had front porches. And people were told to just sleep outside on the porch when they were sick.”

But Warwick residents soon woke up when the Spanish Flu, a misnomer since it is believed that it actually originated in Kansas, began impacting this area. (The pandemic took its name because media outlets in Spain were among the first to report on it.)

In October 1918, The Warwick Advertiser published a front page article titled, Uncle Sam’s Advice on Flu, which described the disease as worse than poison gas and featured some of the same precautions we are taking today. And many of the obituary notices in the paper at the time listed influenza as the cause of death.

At that same time the paper reported that, “Owing to the many cases in the village, the opening of public schools, theaters, churches, dances, fraternal organizations and all other public gatherings is forbidden.”

Does that sound familiar?

In those days the disease struck more young people than older citizens and residents were shocked when they learned that Francis Buckbee, 17, had passed away.

“She was my aunt,” said Warwick Dairy Farmer Al Buckbee. “My father, Wisner Buckbee, also came down with influenza at that time, but he survived.”

Buckbee believes his aunt’s boyfriend had just returned from the war and may have carried the virus, like many other soldiers.

More American soldiers, sailors and marines would succumb to influenza and pneumonia than would die on the battlefields of World War I.

During his program, Hull added that it killed more people in a year than AIDS has killed in 40 years and more than the bubonic plague killed in a century.

Warwick, he said, was fortunate because in 1916, Dr. M. Renfrew Bradner had established the first hospital in this community and with 21 beds, it served the community well during the pandemic.

Many of the residents were also farmers, self-sufficient and practicing social distancing during work as a way of life.

But they did enjoy getting together at Grange parties and that had to be canceled.

Many other residents had heeded the request of the War Department to dig “Victory Gardens” in their back yards and they, too, were self-sufficient when it came to food.

Today, Hull explained, the good news is that we have more hospitals, better hygiene and medical knowledge, especially in the field of bacteriology. The 1918 influenza virus, for example, was not identified until 1933.

“We have more tools today,” he said, “but we also have more mobility.”

People travel all over the world by air in a matter of hours. And it was common in 1918 for many residents, except for those in military service, to have never traveled outside of Warwick.

During his broadcast Hull also mentioned that there are some who believe President Woodrow Wilson, who became seriously ill during the time he was in Europe after the war ended for peace treaty negotiations, may have suffered from the pandemic.

And that in turn may have contributed to the poor treaty, which led to the rise of Adolph Hitler and World War II.

Imagine that.

Contributing to research for this article were Town of Warwick Historian Dr. Richard Hull and Deputy Town of Warwick Historian Sue Gardner.