A girl grows in Sugar Loaf

by Ginny Privitar

Thanks to Clark Holbert, the former Town of Chester Historian, we’re able to tell the story of Lillie Belle Smith, who in 1949, at 81 years of age, wrote “My Childhood in Sugar Loaf, N.Y.”

Holbert preserved her 20-page missive to the future, now in the collection of the Chester Historical Society. It tells about Lillie's adult life. But the portion about her girlhood takes us to a starkly different time, when everybody in a farm family did hard physical labor, when water came by pail, not pipe, and tuberculosis claimed many lives, including those of children. But life in Lillie's rustic hamlet offered many splendors too, and she found time amid her chores to cherish them.

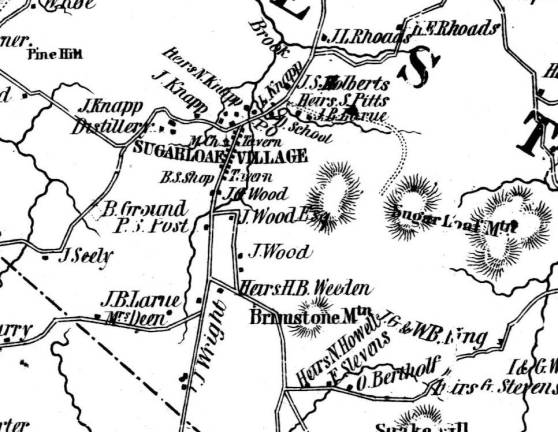

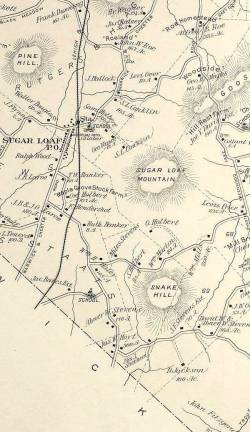

Lillie Belle Smith was born in 1868. When she was five months old, in 1869, the family moved to the John Wood farm in Sugar Loaf to live with their widowed aunt, Peggy Wood. There they stayed for 12 years. When Aunt Peggy died, in 1881, she gave half the farm to Lillie’s mother, who had been like a daughter to her.

“Our farm consisted of about 75 acres of good land and about 20 acres of woodland, which extended to the top of Brimstone Mountain near Sugar Loaf Mountain,” Lillie wrote.

The farm eventually came to be known as the Maple Grove Stock Farm, after Lillie’s father started raising horses. It included an apple orchard among other fruit trees and mature maples.

“There was a large wooden bridge over the railroad track that spanned the fields of our farm,” Lillie wrote. “On the lane leading to the mountain, there was a spring, always clear, cool, and refreshing. How much we enjoyed drinking from it.”

At other times they would get water from their well, which was closer but not as delicious.

When she was six years old, Lillie attended the Sugar Loaf School, wearing a “cute little yellow sunbonnet.” Her best friends were Julia Sweezy, Becky Doleson, and Alice Greer. She remembers her “good and kind” teacher Miss Knapp.

“I can remember my first lessons in the Primer — 'An Ox' — 'It is that Ox'; 'Ann Lee, She is by the Sea'; 'Page Grey, Shut the Gate.' I loved to go to school.”

Like other schools of the time, pails of water were carried in daily from a house nearby.

“This was passed around, each pupil drinking from the same dipper," Lillie recalled. "We played 'Drop Handkerchief,' 'Duck the Rock,' 'Blind Man’s Bluff' in a dark hall. Also 'Hucky Chuck' and 'Grandmother Tipsey Toe.'"

And, of course, they walked the long way to school, except on snowy or rainy days.

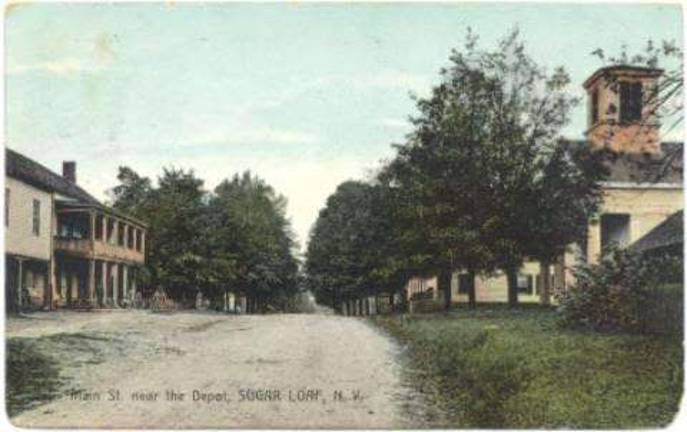

“This was about a mile and thru the small village," Lillie wrote.

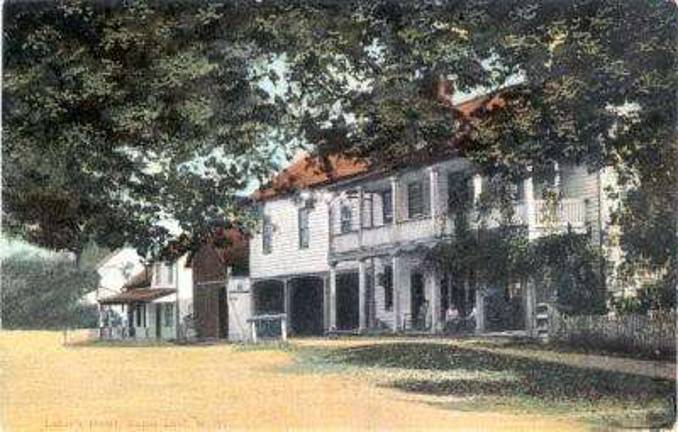

Life on the farm wasn't easy. To supplement their income, the family took in boarders, which added to their chorse.

“We all had to work hard with such a large family," Lillie wrote. "The borders had the table set for them in our sitting room. Our family ate with the hired man or men in the kitchen by the hot stove. So different from nowadays with gas and electricity to make work easier. We had to heat our irons on the stove and carry them back and forth.”

Theboarders meant extra washing — by hand: “12 sheets alone for them and our clothes and hired men’s soiled clothes.”

"How my father grieved to lose his only boy,” Lillie wrote. “He was buried in the cemetery on the farm," with other family members.

Some — including a beloved sister, Bertha or “Birdie,” who was just 20 years old when she died — were buried in the Florida cemetery. Tuberculosis was deadly, and rife.

“Our sister Birdie used to walk up and down the road playing the accordion — she was so musical," Lillie recalled. "At that time, a girl could learn to dress make, learn millenary, or school teaching. Birdie would have liked to be a dressmaker, but we all seemed have our share to do in the house."

Lillie also painted a vivid portrait of her Aunt Sally Wood, who died February 1885.

“Our Aunt Sally was a very tall, thin woman wearing hoops," Lillie wrote. "She never discarded them. We used to go often to see her. She would usually give us some of her good cookies. She wouldn’t let us use a knife and fork, only a spoon, for fear of cutting ourselves or putting out our eyes. She was an odd character, but we liked her funny ways....She was buried in the graveyard on our farm. She used to say 'It will be nice to lie there and hear the trains go by.' She said funny things like that....She used to snuff. She was a dear old soul.”

“Our father bought a fine new sleigh and bells," she wrote. "What fun we had riding in it."

Lillie continued: “About this time, when I was around eleven, Emma Durland was married to Ben DuBois of Chester, New York. The wedding was in the Sugar Loaf Church....I had been riding down the hill on the crust of snow previously, and had fallen off, scratching my nose and face. I must have looked a sight, but I remember it all so well.”

The family owned horses, chickens, and cows. The girls helped with the milking. They had a mare bred to Polonius — sired by history's most famous standardbred, Hambletonian — who won the two-year-old race in 2:42 at the Goshen Race Track.

School always involved a trip.

“On March 5, 1884, I started going to Warwick School,” Lillie wrote. “I walked to Lake Station to get to the train about 9 a.m., as it didn’t stop at Sugar Loaf. There were eleven of us in all. Mr. Harring was the conductor. All said that I was his pet. He once said, ‘Too bad that such a pretty girl should be round shouldered.’

“I took (sister) Lucy with me one day and we had our pictures taken together by a Photographer Towle. How we should like to see it now.”

The family took a trip to the city to visit the Mapes and Haring families in Brooklyn.

“One afternoon, Frank (Mapes) hired a two-seated sleigh and a fine horse," she wrote. "He took us for ride through Prospect Park. Edith took us to the big stores. After staying there a week, we went to visit the Harings, who lived up the street. Their son was very much interested in photographs — just being invented. We were glad to be entertained by them. We had to let the folks at home hear about it.”

Thanks to the writings of Lillie Belle Smith, and the care of Chester's historians, we are indeed able to “hear about it." And, thanks to Lillie's fine descriptive writing, we can see it too — a rare glimpse into one woman’s history on Brimstone Mountain, in a little hamlet that never lost its magic.

Editor's note: A special thank you to Chester Town Historian Clif Patrick for making the archives of the Chester Historical Society available for this story.