John Ruszkiewicz, president of the Drowned Lands Historical Society, was going through the files one day and found a lost soldier.

He came across an envelope he didn’t remember and tucked inside was the diary of a private named Robert Henry Walker.

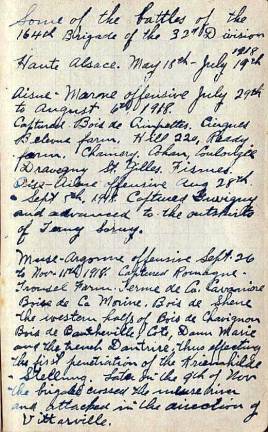

In the small notebook Walker’s cramped handwriting told of his daily life in service from late 1918 to his discharge in May 1919. He also listed the battles he and his unit were in, earlier in the war.

According to World War I historian Aaron Lefkowitz, Walker’s unit was part of the 32nd Division, the “Red Arrow.” It was the only unit given a nom de guerre, “Les Terribles” for their ferocity and relentlessness.

His induction papers show that he was in the “machine gun” division. Among their action was the Aisne-Marne Offensive. He survived many combat situations and was part of the breaking of the “Hindenburg Line.”

During the early postwar occupation of Germany, the time the diary covers, he traveled from England to France, then marched to Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. His brother Fred, who had also been in service, was ill and returned to the states, dying in January 1919 while Robert was in Germany.

Today we have fresh awareness of how painful it is to not be with loved ones when they pass.

In the diary, Robert’s concerns are mainly with food and comfort. One can imagine that having been through the horrors he had previously experienced, this simple recital of details would have helped him orient himself once more to a world in which deadly combat was no longer part of the day. Here is one of his entries, on the boat as they returned home:

“Friday May 9th, 1919 Eggs, liver, oatmeal, bread, butter and coffee for breakfast. It sure is rough sailing today I have got pushed off my feet about a dozen times so far. A fellow wonders now if he will ever get home. Roast meat, peas, potatoes, bread pudding for dinner. The wind is blowing hard and it sure is rough now. Beans, prunes and tea for supper. Very rough all night, hailed and rained.”

How this soldier’s simple recording of camp life during the “mop up” came into the possession of the late Frances Sodrick, former Pine Island Historian and founder of the Drowned Lands Historical Society, is anyone’s guess. Robert Henry Walker lived in the Hartford, Conn., area while he was growing up and his entire adult life; he had no connection to our area that we could find. He worked in the paper industry, married Frieda, and had three daughters. He died in 1948 and is buried in Northwood Cemetery in Windsor, Conn.

Not so long ago we would have been dismissive of his faithful recitation of mundane detail; yet now we see his accounts in a fresh light: What daily details will we who have experienced the pandemic of 2020 record in future years, in gratitude for small things and a day lacking in fear and struggle - piecing the world back together by means of bread, butter, and coffee?

Thanks to the vigilance of another soldier, John Ruszkiewicz, Robert Henry Walker’s diary will be returned home, as part of the archive of the Connecticut Historical Society, where his story belongs.

Sue Gardner is the deputy Town of Warwick historian and reference librarian at the Albert Wisner Public Library.